New to the column? We’re doing a close reading of Genesis, which started in September 2022. Visit the Archive and plunge in, or look here to get oriented.

We’ll return to our close reading of Genesis on Tuesday. Today, we’re going to spend some time talking about the Iron Age. When you read the next few verses in Genesis 4, it seems as if civilization is off to the races. So today’s focus is on the invention of technology.

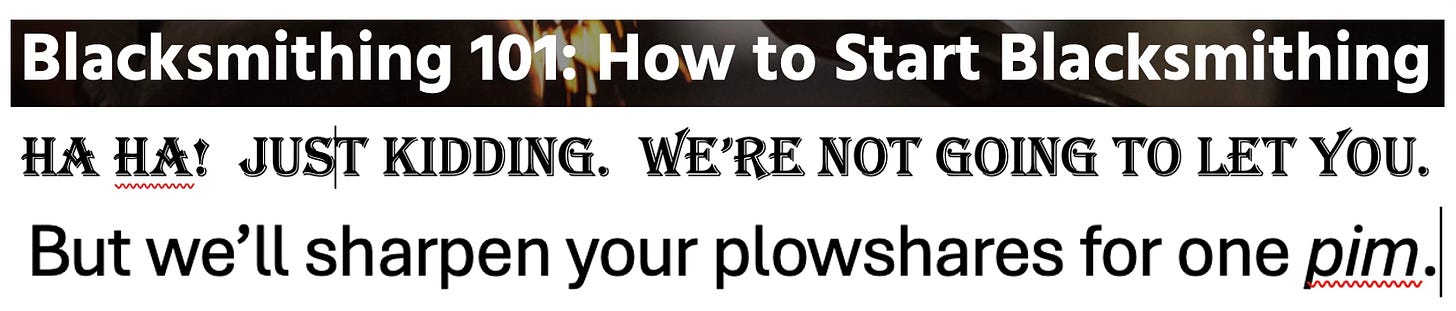

But first — this message from the Philistines:1

Last time, as you recall, we discussed the two wives of Lemekh, of whom (translating literally) “the name of the one was Ada, and the name of the second was Zilla.” We mentioned then another example of one man married to two women, from 1 Sam 1:2, where a similar expression gives us the names of Elkanah’s two wives, Hannah and Pnina.

But I took things a little further, pointing out that both that story and this one are set in a period of anarchy. Hannah’s son (whether Samuel or Saul) will put an end to that period of anarchy, just as Noah, the son of Lémekh in Genesis 5, will survive the end of this one. In 1 Samuel, the enemy of the Israelites is the Philistines.

The whole point of their big ad campaign (as devised for them by me, above) is that — according to 1 Samuel 13 — the Philistines had entered the Iron Age before the Israelites were able to do so. They had a technological advantage that gave them weapons capability, and they were laser-focused on making sure that the Israelites could not develop the same capacity. (Sound familiar?)

Here's the relevant passage in 1 Samuel (in the NJPS translation). Saul (or his son Jonathan) has just killed the Philistine administrator (the netziv) and had the shofar sounded to summon the Israelites for the expected battle. Samuel, the high priest, prophet, and (until Saul came along) ruler of Israel, picks just this moment to tell Saul that he’s fired as king. Then the news report resumes, with a crucial bit of background information:

1Sam. 13:19 No smith was to be found in all the land of Israel, for the Philistines were afraid that the Hebrews would make swords or spears. 20 So all the Israelites had to go down to the Philistines to have their plowshares, their mattocks, axes, and colters sharpened. 21The charge for sharpening was a pim for plowshares, mattocks, three-pronged forks, and axes, and for setting the goads. 22 Thus on the day of the battle, no sword or spear was to be found in the possession of any of the troops with Saul and Jonathan; only Saul and Jonathan had them.

Now a quick preview of what we’ll read coming up in Genesis 4:

Jabal will be the “ancestor” of nomads who herd livestock (v. 20).

Jubal will be the “ancestor” of the musicians (v. 21).

Tubal-Cain will forge implements of copper and of iron (v. 22).

Shubert Spero writes:

Each one of the above discoveries or inventions constitutes a definitive game changer in the development of human culture.

Thinking out loud here … in the Genesis 5 genealogy, Noah of Generation 10 is followed in Generation 11 by three sons who will go on to populate the three continents of the world: Europe, Asia, and Africa. Here in Genesis 4, Lemekh of Generation 7 is followed by three sons who will begin various branches of civilization. (Lemekh has a daughter as well, whose name we know, but the text tells us nothing else about her.)

If we suppose that Cain was indeed semi-divine, we can understand him as an ancient Near Eastern Prometheus. And that seems to be part of what’s happening here in Part 2 of Cain’s story. (Yes, he’ll be back in v. 24.) We mentioned this part of the story a few months ago when we discussed etiologies, and it seems quite clear that Lemekh’s children fall more or less into the etiology category.

Yet it’s also clear that the beginnings of civilization are not what’s at issue here. Even if these innovators originally had “Just So” stories attached to them, the stories are not included here. There is a story here that Rudyard Kipling might possibly have called “Why People Started Getting Dressed,” but that title seems to miss the point. That’s certainly not what Genesis 2–3 are in the Bible to explain.

One of the questions that arises when we study the Bible is: At what point do the biblical stories shift from being more legendary to more historical? The book of Samuel is one reasonable answer to that question, and the picture of Philistines controlling the new iron weapons technology is certainly a plausible one.

Whether or not that’s true, the Iron Age in the Fertile Crescent (and in the ancient Near East in general) began long after the story of the Israelites that we’ll start to read in Genesis 12. If Tubal-Cain is forging implements of iron in Genesis 4, then either this story has been moved back thousands of years in history, or its purpose is not factual.

What I believe it’s doing is picturing civilization growing by leaps and bounds — after the 7th generation of humanity, per Genesis 4, which would seem to point to a second stage of development, where human settlements are growing larger and more complex, changing from isolated villages into societies. Anthropologists (I believe) would tell you that what accompanies this development is more inequality and more violence. That’s the heritage of Cain the city builder.

Spero points out that …

… the text clearly associates Cain, a name almost synonymous with sin and fratricide, with one of the giant steps in human development, the formation of urban society with all of its economic and political ramifications such as the development of trade, resident crafts and centralized government.

We’ve already seen that the story of Cain’s killing of Abel is told in a way that implies the existence of cities. I don’t see that Genesis 4 is writing in favor of this development, or against it either. What’s happening is that a more complicated background is taking shape while we watch the events that happen in the foreground.

A Flood is coming up that will destroy civilization, which can’t logically happen until civilization exists. The etiologies of (for example) Greek legends are explaining why the world is the way it is. The etiologies of Genesis are doing a very different kind of narrative work.

Next time, we’ll get back to the details and begin to look at Lemekh’s children.

h/t to https://www.thecrucible.org/guides/blacksmithing/ where I copied this headline.

Just after the column was posted, this new book announcement crossed my desk (h/t Jack Sasson). For those who have $170 burning a hole in their pocket:

From <https://www.routledge.com/The-Dawn-of-Agriculture-and-the-Earliest-States-in-Genesis-1-11/Levy/p/book/9781032446882>:

============================

The Dawn of Agriculture and the Earliest States in Genesis 1-11

By Natan Levy

Hardback, $170.00

eBook, $47.65

ISBN 9781032446882

218 Pages 10 B/W Illustrations

This book invites a close textual encounter with the first 11 chapters of Genesis as an intimate drama of marginalised peoples wrestling with the rise of the world’s first grain states in the Mesopotamian alluvium.

The initial 11 chapters of Genesis are often considered discordant and fragmentary, despite being a story of beginnings within the context of the Bible. Readers discover how these formative chapters cohere as a cross-generational account of peoples grappling with the hegemonic spread of domesticated grain production and the concomitant rise of the pristine states of Mesopotamia. The book reveals how key episodes from the Genesis narrative reflect major societal revolutions of the Neolithic period in Mesopotamia through a three-fold hermeneutical method: literary analysis of the Bible and contemporary cuneiform texts; modern scholarship from archaeological, anthropological, ecological, and historical sources; and relevant exegesis from the Second Temple and rabbinical era. These three strands entwine to recount a generally sequential story of the earliest archaic states as narrated by non-elites at the margins of these emerging state spaces.

The Dawn of Agriculture and the Earliest States in Genesis 1–11 provides a fascinating reading of the first 11 chapters of Genesis, appealing to students and scholars of the Hebrew Bible and the Near East, as well as those working on ecological injustice from a religious vantage point.